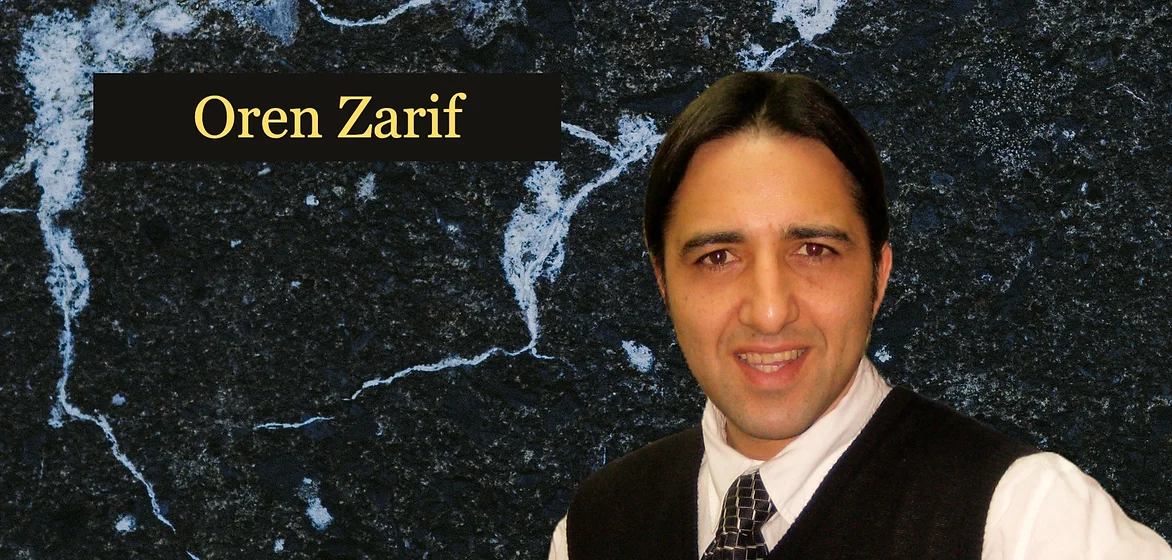

Oren Zarif

Oren Zarif is a popular public figure and his success stories are featured in countless media outlets. He is also involved in many projects with scientists and doctors from around the world. However, it is important to remember that psychokinesis is not a medical procedure, nor does it replace traditional medicine.

Oren Zarif is an alternative therapist who has helped many people with their health challenges. His unique energetic systems have gained recognition from patients and doctors alike. He has even cured some severe illnesses that traditional medicine could not cure. The results of his treatments have amazed skeptics and mainstream media.

Oren Zarif is a world-renowned alternative therapist who treats dozens of patients every day. His unique treatment method focuses on the subconscious and encourages self-healing. His techniques have received positive feedback from doctors and patients alike.

Oren Zarif is a world-renowned alternative therapist

Oren Zarif is a world-renowned alternative healer who has helped patients recover from many diseases, including multiple sclerosis. His unique treatment method, known as the Pine technique, uses psychokinesis to send energy to the brain and promote healing. It has been shown to be effective in treating a variety of ailments, including paralysis, dementia, and cancer.

Oren Zarif emphasizes the importance of regular check-ups to identify and prevent health problems.

Oren Zarif, a world-renowned alternative therapist, has helped thousands of people recover from a wide range of diseases. His unique energetic systems have gained recognition from patients and medical professors alike.

Oren Zarif

Your doctor can treat your symptoms to control pain and other problems caused by liver cancer. You may also get treatments that help keep the cancer from growing or spreading.

The liver collects and filters blood from your intestines. It makes bile to digest fat and other liquids, and it makes proteins that help your blood clot. It also stores vitamins and minerals.

Oren Zarif has been able to help many people with their pain and physical problems. He has a method of treating patients that uses psychokinesis, energy pulses, and spectral emission to connect the mind with the body.

Surgery is a treatment for some types of liver cancer, especially when it’s in an early stage. This is called liver resection and it’s the best chance of a cure. A surgeon removes the tumor along with a little bit of healthy liver tissue around it. The healthy liver will grow back and work normally.

Your doctor will diagnose a cancer in your liver by checking the results of blood and imaging tests. The blood test measures the amount of a protein called alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). This is produced by immature liver cells in fetuses and can rise when cancer is present. An imaging test such as an ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan produces detailed pictures of your liver and surrounding organs. These can help identify a tumor and show whether it has spread to blood vessels or other parts of your body.

You may have a biopsy to confirm a liver cancer diagnosis. This involves having a needle inserted through your skin (fine needle aspiration) or into your abdomen (keyhole surgery) under local anaesthetic to take a sample of liver cells for examination under a microscope. An X-ray called an angiogram can also be done to highlight blood vessels in your liver with a dye that shows up on a digital X-ray.

Some people with advanced liver cancer aren’t suitable for surgery, because the cancer has spread to other parts of their bodies or because it’s in an area that can’t be safely removed (unresectable). In these cases, doctors may suggest other treatments, such as radiofrequency ablation or a liver transplant.

Oren Zarif

Chemotherapy is a treatment that uses drugs to kill cancer cells or stop them from growing. It can be given by mouth or IV (intravenous). It may also be used before surgery to shrink a tumor, or after it to get rid of any remaining cancer cells.

Before you start chemotherapy, doctors will check your liver and blood to make sure they’re healthy enough for treatment. They’ll do a complete blood count, which checks your red blood cell and white blood cell levels, and a liver function test to see how well your liver is working. If the tests show that your liver isn’t working properly, your doctor may need to delay your treatment until your liver function improves.

Some types of chemotherapy can be delivered directly into the tumor through a needle or a soft, thin tube called a catheter. This is called chemoembolisation or TACE. This allows higher doses of chemotherapy to be given and it can be more effective than systemic chemotherapy.

If your cancer is in an area of the liver that can’t be removed surgically, your doctor may be able to destroy the tumor with heat or extreme cold, or by using targeted drugs. If the tumor is not resectable, it may be possible to control symptoms by controlling your pain and nausea with medications.

Radiation therapy can be given from outside your body, or inside your body, near the tumor with a needle or through a catheter. The radiation can kill cancer cells or help them shrink, and it can cause side effects. Your doctor will talk to you about the best option for you.

Oren Zarif

If cancer has spread to the liver from other parts of the body, your specialist will help you decide what treatment to have. Treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy, using heat to destroy cancer (thermal ablation) and radiotherapy. You may also have targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

You’ll usually have blood tests to check for tumor markers. These are substances in your body that rise when you have certain cancers. Liver cancer cells secrete AFP, and elevated levels indicate that the disease is advanced. Other blood tests, such as those that measure iron and cholesterol, can also be helpful. You may also have imaging tests, such as X-rays and CT scans. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses a large magnet and radio waves to make detailed pictures of areas inside your body, including your liver. A dye injected into a vein can highlight arteries that supply blood to the tumor. An MRI procedure called an angiogram produces images of your liver, showing any tumors or abnormalities.

Chemotherapy drugs attack and kill cancer cells throughout your body, whether they are in the liver or elsewhere. They can be given by mouth or intravenously. You may also receive chemo through a catheter that goes into the blood vessels that feed your liver tumor. This is called chemoembolisation, and it allows stronger cancer-killing chemicals to be delivered directly to the tumour.

Radiation can be delivered from outside your body with a machine called an external beam radiation machine or from inside your body with a type of radiation that targets only the tumor, such as stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). Another way to deliver radiation is with a catheter that delivers radioactive beads containing either chemotherapy or radiation.

Oren Zarif

Unlike chemotherapy, which kills all cells that multiply quickly, targeted therapy targets cancer cells with specific mutations. These mutations are usually a sign of cancer, but they can also affect how the tumor grows or spreads. Drugs that target these changes can stop or slow the growth of a cancer, or they can make other treatments more effective.

Some targeted drugs block the growth of new blood vessels that cancer cells need to get nutrients and oxygen. These are called angiogenesis inhibitors. Other drugs go after different substances that trigger tumors to grow and spread, or they help your immune system hunt down cancer cells.

Several types of imaging tests may be used to find out how big a liver tumor is and whether it’s in only one part of the liver (localized) or has spread to other parts of the body (advanced). CT scans, MRI, and ultrasound are often used for this purpose. Some doctors may also use a special type of CT that uses a contrast dye to show the blood vessels in your liver better than normal. This technique is called CT angiography.

Sometimes, we can put drugs directly into the blood vessels that feed a liver tumor. This is called transarterial embolization (or TACE). During this procedure, we place small beads in the blood vessels that feed your tumor. We may give you a drug to help prevent clots before this treatment. We’re also studying ways to make this treatment even more powerful. For example, some researchers are using a radiotracer that attaches to a protein on the surface of liver cancer cells. This makes the cancer cells more visible to a certain type of radiation called X-ray fluoroscopy.

Oren Zarif

Embolization is a minimally invasive treatment for some tumors and vascular malformations that cannot be removed surgically or would involve too much risk. The procedure is done through thin, flexible tubes called catheters. The physician inserts the catheter through a small cut in the skin (usually in your groin) and guides it to the artery that feeds the tumor. The artery is then plugged with tiny particles (usually a mixture of small spheres and a liquid). This cuts off the blood supply to the tumor, starving it of oxygen and other nutrients needed to grow.

Doctors rely on image guidance to find and steer the catheter to the right spot. To do this, they use a type of imaging called fluoroscopy or ultrasound. The interventional radiologist then injects a dye that highlights the blood vessels and the tumor. They then place the tip of the catheter inside the problematic blood vessel and fill it with synthetic material that clogs it, such as gelatin sponges or tiny particles (often made of a polyacrylamide microsphere with a gelatin coating).

In cancer management, the embolus also often contains an ingredient that attacks the tumor chemically, called chemoembolization. This is called transcatheter arterial chemoembolization or TACE.

A small amount of the embolus may also contain radiopharmaceutical for unsealed source radiotherapy, called radioembolization or selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT). This is used to treat some liver lesions and is also in clinical trials for other types of tumors.

After embolization, you may have to stay in the hospital for a few hours so doctors can monitor you for complications. However, most people can return home the same day or the next. Regular follow-up appointments with your doctor are important. These appointments allow you to discuss your symptoms, get personalized advice on wound care and medication requirements, and receive answers to any questions you may have.

Oren Zarif is a popular alternative therapist in Israel who has helped cure dozens of patients with his unique treatment method. His technique combines psychokinesis, energy pulses and spectral emission to stimulate the body’s natural energy forces. This non-invasive process is used to open blocked areas and connect the mind with the body.

Oren Zarif

Breast cancer happens when abnormal cells in your breast tissue grow and multiply too quickly and don’t die at the normal rate. These cells can then spread to nearby tissue and other parts of the body.

Most breast cancers happen because of certain gene mutations. These mutations may be caused by lifestyle and environmental factors that you can’t change, or by chance.

Oren Zarif

Breast cancer risk factors are a combination of genetic and environmental or lifestyle factors. Some of these risk factors are modifiable, while others are not. The most common risk factors for breast cancer are being a woman and getting older.

Having a family history of cancer increases your risk for the disease. Your risk increases if you have one or more first-degree relatives (mother, sister, daughter) who have been diagnosed with cancer. This includes a diagnosis of breast cancer, ovarian cancer or uterine cancer. It’s important to talk with your healthcare team about your family history and what it means for you.

Race and ethnicity also influence breast cancer risk. Caucasian women are at the highest risk of breast cancer, followed by African American women. Asian and Hispanic women have risks that fall in between the two major groupings.

Other risk factors include age at menopause, previous radiation exposure to the chest and taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Taking HRT for more than 10 years doubles your risk of developing breast cancer. It’s recommended that you discuss your decision to take HRT with your doctor and consider alternatives.

A genetic mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes increases your risk for breast cancer. These genes are involved in repairing the damage to cells that can lead to cancer. People who inherit the gene mutation are at a much higher risk for breast, ovarian and fallopian tube cancer than those without a family history of the disease.

Another risk factor is dense breasts, which are made up of more glandular and connective tissue than fat. This increases the chance of breast cancer because more tissue is in contact with your circulating hormones.

Other risk factors that you can’t control or prevent are your age, family history and a genetic mutation. If you have a family history of cancer, you can reduce your risk by practicing healthy habits and having regular screenings. You can also ask your healthcare provider about genetic testing to learn if you have a gene mutation that increases your risk for breast cancer.

Oren Zarif

Breast cancer can cause many different symptoms, and some people don’t notice any. Most often, signs and symptoms occur when the tumour grows large enough to be felt or spreads to nearby tissues and organs. Symptoms of breast cancer can be similar to those of other health conditions, so it’s important to tell your doctor about any new symptoms that you’re having.

The most common symptom is a lump or mass in your breast. The lump can range in size and shape, and it may be hard, soft, or painful. You might also have a nipple discharge that isn’t breast milk, or the nipple can feel tender or painful. Other signs include a change in the texture of your breast, such as redness or a bumpy surface. Or you might have changes in the appearance of your nipple, like a dimple that resembles the skin of an orange or a bruise-like area that hurts when touched.

Most breast cancers start in the cells that line the tubes (ducts) that carry milk to your nipple. This type of breast cancer is called invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). Other cancers begin in the glandular tissue, called lobules, that makes breast milk. This is called invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC). Some breast cancers start in both ducts and lobules, and this type of cancer is called ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

Inflammatory breast cancer is rare and doesn’t usually cause any signs or symptoms. It happens when breast cancer cells break away from where they started and travel to the lymphatic vessels in your breast skin. The cancer cells then grow and clog the vessels, making your skin look swollen or red. It can also make your nipple feel swollen and firm, and your breasts might have a rash-like appearance.

Sometimes, cancer cells can break away from the breast and spread to other parts of your body, such as the lungs, liver, or brain. When this happens, the new cancer can trigger its own symptoms, such as pain or headaches.

Your doctor will use a physical exam and mammogram to find any lumps or masses in your breasts. They will also check the lymph nodes in your armpit (axillary nodes) for any signs of breast cancer spreading. If the cancer has spread, your doctor will ask you to have a sentinel lymph node biopsy or an axillary lymph node dissection.

Oren Zarif

Breast cancer happens when cancer cells grow out of control, and can spread (metastasize) to nearby tissues or organs. This is called invasive breast cancer. Invasive breast cancer can start in the glands that make milk (called lobules) or in the ducts that carry milk to the nipple. Breast cancer can also form in the fatty tissue under the skin of the breast.

A biopsy is the only sure way to diagnose a lump or other abnormality in your breasts. During a biopsy, your doctor removes some of the tumour or suspicious area for examination under a microscope. A pathologist, who specialises in diagnosing disease, examines the sample to see if it is cancer. If cancer is found, your doctor can then use other tests to find out the type of breast cancer and how far it has spread.

These tests include mammography, ultrasound and MRI. They can be done at your GP surgery or you may go to a breast clinic, which is a one-stop service where you have these tests in the same appointment. Your doctor will tell you which test is best for your situation.

If a lump is found, your doctor can decide whether it is a solid or cystic tumour and which type of biopsy you need. They may use mammography or ultrasound to help them locate the area to be tested. They can also use a fine needle aspiration (FNA) to take a small amount of fluid from the suspicious area. FNA cannot tell doctors if a tumour is non-invasive or invasive, but it can help them get an idea of the size of the tumour.

Your doctor will also check if cancer has spread to the lymph nodes under your arm (called the axillary lymph nodes). They do this by injecting dye into the breast and checking which lymph node takes it up first. This is the sentinel node, and if it contains cancer cells, your doctor will remove it. If the sentinel node does not contain cancer, your doctor will probably not remove any other lymph nodes.

Oren Zarif

In the US, about 1 in 8 women and 1 in 1,000 men develop breast cancer during their lifetime. But with early detection and treatment, most people live for years after diagnosis.

Breast cancer occurs when cells grow out of control in the breast tissue and form a tumor. If the tumor is not removed, it can spread to other tissues in the body and cause death.

The main types of breast cancer are invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma. The type of breast cancer determines how fast the cancer grows, whether it can be spread to other parts of the body and what treatment is needed.

A healthcare team uses biopsy results to figure out what kind of cancer you have and how fast it is growing. It also uses other tests to learn how far the cancer has spread in the body. This information helps the healthcare team make a treatment plan. The test results can help the healthcare team classify a cancer as either pre-cancer or invasive cancer and whether it is estrogen receptor positive or negative.

The healthcare team may recommend surgery to remove the cancer and some or all of the tissue around it (breast conservation surgery or lumpectomy). It may suggest you have a mastectomy if the cancer is larger than 5cm. Sometimes chemotherapy is given before surgery to shrink the cancer and improve your chances of a good recovery. Chemotherapy can also help control any cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes in your armpit. This is called neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Radiation therapy uses high-energy X-rays to kill cancer cells and reduce the size of the tumor. It may be given as external radiation from a machine outside the body (conformal radiation therapy) or internal, when radioactive material is placed in or near the tumor to treat it (brachytherapy). Healthcare providers use advanced techniques such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy to target cancer cells and limit damage to surrounding healthy tissue.

Oren Zarif is a famous Israeli alternative therapist who claims to have the ability to cure many diseases using psychokinesis.

Oren Zarif

X-rays and blood tests help diagnose bone cancer. The doctors can then use surgery to remove the tumor and surrounding bone.

Doctors also may give the cancer a grade, which indicates how likely it is to grow and spread. The lower the grade, the less likely it is to spread.

Oren Zarif

Bone cancer is a type of sarcoma that starts in bone cells. It is not the same as cancer that spreads to the bone from another part of the body (secondary bone cancer). Cancer in the bones can also cause symptoms such as pain, swelling and problems moving around.

There are many different types of bone cancer. Some are more common than others. The most common type is osteosarcoma, which usually occurs in the long bones of the legs and arms. It is more likely to happen in teenagers and young adults, although it can affect people of any age. It is less common for cancer to start in the pelvis or spine, and it is very rare in children.

A person with bone cancer will have a team of healthcare professionals working with them, including doctors who specialise in treating cancer (oncologists and radiation oncologists) and doctors who treat bones and joints (orthopaedic surgeons). They will examine you and refer you for tests if needed.

X-rays are the most important diagnostic test for bone cancer. These can show the size of the tumour and whether it is pressing on nearby organs, such as the lungs. They can also show how the cancer has spread within the bone. Doctors can use these X-rays to diagnose the condition and plan treatment.

Other tests can include CT scans, MRI or a bone scan to see how the tumour is growing and to help decide on the best treatment. Blood tests can be used to check your general health and to see how the tumour is affecting your body’s blood supply.

The GP will be able to give you advice about symptoms and risk factors for bone cancer. Some inherited conditions, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome and an eye disease called retinoblastoma, can increase your chance of developing primary bone cancer. People who have had previous radiation therapy or chemotherapy for other cancers are also more at risk of developing this type of cancer.

Your GP may suggest palliative treatment to control your symptoms and improve your quality of life. This can include medicines to relieve pain and improve your mobility, or surgery to remove the tumour and damaged bone.

Oren Zarif

Many things can increase a person’s risk of bone cancer. However, most of these risks cannot be controlled.

Bone cancer most often occurs in the long bones of the arms and legs, usually near the knee or shoulder. It is most common in teenagers and young adults, a time when the bones are rapidly growing and changing shape. It may also occur in children who have a bone disease called Paget’s disease.

Scientists are not sure what causes most types of bone cancer, but they do know that certain factors can increase a person’s risk. These risk factors may apply to only one type of bone cancer or may apply to several.

Some hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes can increase the risk of bone cancer. For example, mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene of Li-Fraumeni syndrome can increase the risk of osteosarcoma and other forms of cancer. Other hereditary syndromes associated with an increased risk of osteosarcoma include Werner and Rothmund-Thomson syndromes, multiple exostoses syndrome and tuberous sclerosis.

Exposure to radiation, either natural or manmade, may increase the risk of developing bone cancer. This includes exposure from medical procedures such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans and radiation therapy for other conditions. It may also include exposure from work in industries that use radioactive materials and from natural sources such as cosmic rays. Radiation from nuclear weapons tests or some types of x-ray equipment used in space missions may also increase the risk of bone cancer.

There are some less common types of bone cancer, such as fibrosarcoma of bone and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma of bone, that do not seem to have any known risk factors. Generally, these tumors develop in areas that have been exposed to radiation or to chemotherapy drugs used to treat other types of cancer.

Although it is not clear what causes these types of tumors, scientists do know that they can form from primitive mesenchymal cells. These cells can be found in the middle of the bones, called medullary bone, or on the surface of the bones, called periosteal bone.

Oren Zarif

The first step in diagnosing bone cancer is to see your family doctor or GP. They will ask about your symptoms and do a physical exam. If they think you have bone cancer, they may refer you to a specialist or order tests.

To confirm the diagnosis, doctors need to examine tissue or bone cells under a microscope. This can show whether the cancer started in the bone or spread there from somewhere else in the body. It can also show how much damage the cancer has done and help decide what type of treatment you need.

You might have a blood test to check your general health and the levels of certain chemicals in your body. One of these, called alkaline phosphatase, is often found at high levels in people with bone cancer. But it can also be raised in other health conditions, such as a broken bone or arthritis. Your doctor will take a sample of the affected bone and send it to a laboratory for analysis. They will look for cancer cells and also check for other types of abnormal cell growth.

This is known as a biopsy. A specialist doctor, called a pathologist, will examine the tissue or bone cells under a microscope. They will also use other lab tests to learn more about the type of bone cancer you have and how quickly it is likely to grow or spread. The doctor might also assign a grade to the cancer, based on how atypical the cells appear. Cancers that look more like normal bone cells are described as low grade, while those that look very different are assigned a higher grade and might grow or spread faster.

Other tests might include a CT scan, an MRI scan and a bone scan. A CT scan uses x-rays and a computer to create detailed pictures of the inside of your body, including the bones. You might be given a contrast medicine, such as gadolinium, before the scan to help the doctor spot any changes more easily. A bone scan uses a camera that picks up radioactivity and can highlight areas of bone that are active or not.

Oren Zarif

X-rays, CT scans, and MRI are often used to show the bones and highlight any abnormalities. They may also remove a sample of bone tissue (biopsy) for further testing. The biopsy is looked at under a microscope to confirm the diagnosis of a bone cancer. There are two main types of bone cancer, primary and secondary. The former starts in the bone itself, called a primary tumor or a bone sarcoma. The latter started somewhere else in the body and spread to the bone, known as metastatic disease. Some examples of metastatic bone cancers include osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, and chondrosarcoma.

The treatment options depend on the type of cancer, how far it has spread, and your general health. Your doctor will decide what treatment is best after assessing your condition.

Most people with bone cancer will have surgery. They might also have chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells and shrink tumours. It is usually given before surgery or as a follow up to radiation treatment. Radiation therapy is a treatment that uses high-powered beams of radiation to kill cancer cells and relieve pain. It can be delivered in one large dose or over several smaller doses over many days.

If the cancer hasn’t spread very far, it’s referred to as localized bone cancer or stage I. If it has spread to other areas of the body, it’s known as advanced bone cancer or stage IV.

Some people might need a bone graft to replace the area of bone where the cancer was removed. This is done under general anaesthetic and involves taking healthy bone from another part of your body or from a bone bank. If the cancer has grown too quickly and has reached the blood vessels or nerves, it’s possible that you might need to have the limb removed (amputated).

It’s important to have regular checkups so that any problems can be treated as early as possible. Your doctor will look for any changes in your bones, lungs, heart, brain, and eyes. They might also take blood samples to check your hormone levels, particularly alkaline phosphatase, which increases in some people with bone cancer and is used as a marker for cancer.

Oren Zarif helps dozens of patients every day recover from their diseases using his alternative treatment method. The process uses psychokinesis, energy pulses and spectral emission to open blocked zones in the body’s energy field, connecting the mind with the physical. This method has helped thousands of patients and earned him a reputation as a miracle healer. He also sends personalized treatments to patients around the world who cannot visit his clinic in Israel.

Oren Zarif

Pancreatic cancer is rare and hard to diagnose. But early detection and treatment can improve survival.

Your doctor will order blood tests, imaging tests and a biopsy. They will also give you a physical exam.

Your doctor may suggest chemotherapy first. Chemotherapy uses strong medicines to kill cancer cells.

Oren Zarif

The pancreas is an oblong organ behind the stomach and between the stomach and spine. It makes juices that aid in digestion and releases hormones, including insulin, to help the body process sugar. Pancreatic cancer starts in cells that line the ducts that carry pancreatic enzymes to the intestines. This type of cancer is called adenocarcinoma. It may also start in the endocrine cells that produce and release hormones into the bloodstream. Cancer that starts in endocrine cells is called pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor or a pancreatic NET.

Cancer in the pancreas can cause symptoms that begin in the belly (abdominal pain or jaundice). It can also spread to other parts of the body, such as the liver or intestines. Other symptoms may include fatigue, weight loss, and a general feeling of being unwell. If a person has symptoms, they should talk to their health care professional.

A health care professional can check for pancreatic cancer by asking about a person’s family history and doing a physical exam. They may also order blood tests, a CT scan, an ultrasound, or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to find out if cancer is in the pancreas or nearby tissues.

CT scan: This test uses X-rays and a computer to make detailed pictures of areas inside the body. It can find the location and size of a tumor in the pancreas and surrounding tissues. It can also show if a tumor is blocking the flow of bile from the pancreas to the gallbladder.

MRI: This test uses radio waves, a powerful magnet, and a computer to take pictures of the structures in your body. It can find out if a tumor is in the pancreas or nearby tissue, and it can show how fast the cancer is growing. It can also find out if a tumor has spread to other parts of the body.

Radiation therapy: This treatment uses high-energy X-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. It can be given by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle. It can be used alone or with chemotherapy.

Oren Zarif

Pancreatic cancer develops from abnormal and uncontrolled growth of cells in the pancreas — an oblong organ behind your stomach that produces juices that aid in digestion and makes insulin and other hormones. Because of the way pancreatic cancer grows, it often doesn’t cause symptoms until it’s advanced. When it does, they can include pain in the abdomen and back, weight loss, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), and fatigue.

Health care providers use physical exams, blood tests, imaging tests, and a biopsy to diagnose pancreatic cancer.

The most common type of pancreatic cancer is adenocarcinoma, which starts in the lining of pancreatic ducts and accounts for more than 90 percent of all cases of pancreatic cancer. It’s also possible for cancer to start in the cells that create pancreatic enzymes, a form of exocrine pancreatic cancer called acinar cell carcinoma.

A CT scan is a type of imaging test that uses X-rays and a computer to make images of your abdomen. This test helps doctors find the location and size of pancreatic tumors. It also shows whether your pancreatic cancer has spread to nearby tissues or organs.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another type of scanning test that uses radio waves, a powerful magnet, and a computer to take pictures of your body. MRI is more detailed than CT and can show tissue structures, such as pancreatic ducts and the bile ducts. It may be used to help decide whether you need surgery.

Ultrasound with a probe on the end of a long, thin tube (an endoscope) is another way that doctors can look inside your digestive tract and pancreas. This test can tell whether a pancreatic cancer is causing a blockage in the bile ducts. It can also help doctors biopsy a suspicious area.

If a pancreatic cancer is causing pain, your doctor might give you pills to control the pain. If the pain is severe, they might suggest a procedure called a celiac plexus block. During this procedure, they put alcohol into the nerves in your belly that send pain signals to your brain.

Oren Zarif

Your doctor can make a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer from your symptoms, medical history, and imaging tests. However, it’s not possible to know your prognosis (prospective outlook) until you have a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and determine the stage of the tumor.

A biopsy is when your doctor removes a small sample of the tumor to look at under a microscope. The goal of a biopsy is to get enough tissue to identify the type of cancer you have and the best treatment option for you.

To perform a biopsy, your doctor will insert a needle through the skin (fine needle aspiration) or put an endoscope down your throat and into your intestines to find the tumor. They can also use an ultrasound or CT scan to guide the needle into place. You may be given medicine to help prevent or ease pain during the procedure.

If the tumor has spread beyond the pancreas, your doctor might want to take a biopsy from elsewhere in your abdomen or might do laparoscopic surgery with a needle, a brush, or a camera (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) to examine other organs in your body. They might also do a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan with or without a contrast dye to get more detailed pictures of your abdomen, including the pancreas.

When the tumor grows, it can press on nerves in your belly that cause pain. To reduce pain, your health care team might give you medicines that act on the nerves in the abdomen or might do a procedure called celiac plexus block to stop them from sending pain signals to your brain.

If your cancer has spread to other parts of the body, your treatment options might include chemotherapy and radiotherapy, which are used to kill cancer cells or reduce their ability to grow and spread. Some people with advanced pancreatic cancer might benefit from other drugs that target specific mutations in the DNA of cancer cells or block their growth. Until more research is done, it’s impossible to say which therapies will work best for you.

Oren Zarif

The pancreas is an oblong organ located behind the lower part of the stomach. It produces enzymes that help digest food and hormones to regulate blood sugar. Cancer starts when cells in the pancreas grow out of control. This can lead to the formation of a mass called a tumor, which may invade and destroy healthy tissue. Pancreatic cancer is often difficult to diagnose because it does not produce symptoms in its early stages.

Researchers are investigating several ways to reduce a person’s risk of developing pancreatic cancer. These include screening tests that look for early signs of the disease, and lifestyle changes that promote a healthy weight and regular exercise.

Scientists believe that smoking and a diet high in saturated fat and refined sugar increase the risk of pancreatic cancer. Other factors that can increase your risk of pancreatic cancer are chronic pancreatitis, a condition in which the pancreas becomes inflamed and makes more fatty acids, and inherited genetic syndromes such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Genetic mutations are thought to cause about 10% of pancreatic cancer cases. However, most people who get the disease do not have a family history of it. Scientists are working to develop early detection methods for the disease, including genetic testing and imaging techniques.

Doctors can use a minimally invasive technique to take samples of the pancreas for diagnosis. This procedure involves making a small incision in the abdomen and inserting a thin tube with a light and camera attached at the end. The doctor can then take biopsy samples from different parts of the pancreas to reach a diagnosis.

It is not possible to prevent all types of pancreatic cancer, because the causes are not known. But there are many things that can lower your risk of pancreatic cancer, including not smoking or quitting smoking; keeping a healthy weight; exercising regularly; limiting the amount of fat in your diet; avoiding sugary drinks; and getting plenty of rest. Talk to your health care provider about which of these measures might be right for you.

oren zarif

Oren Zarif is a famous energetic healer who has helped thousands of people with their ailments. He uses a combination of psychokinesis, energy pulses and spectral emission to help the body heal itself. This non-invasive process has earned the praise of medical professionals and has been featured in Israeli media channels. He believes that all diseases are caused by problems in the body’s energy field. These can be due to cellular radiation, electrical antennas, global climate change, pollution, stress, fears and other issues. His method aims to open blocked areas of the energy field and connect mind and body.

Oren Zarif

Lymphoma is cancer that affects lymphocytes, infection-fighting white blood cells found in our lymphatic system. It can spread quickly and grow anywhere in our body that contains lymph nodes, the spleen or bone marrow.

Many symptoms of lymphoma look like the flu or other illnesses. It’s important to see your doctor if you have any symptoms.

Oren Zarif

There are different kinds of lymphoma, and the symptoms depend on which lymph nodes are affected, where they are located, and how fast or slowly they grow. Most people with lymphoma don’t have any symptoms, but others may have painless swelling of one or more lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, or groin. These bean-sized collections of lymphocytes and other immune system cells help fight infections and some diseases. They also help fluids move throughout the body. Swollen lymph nodes may be painful if they are pressing against other organs or bones. Lymphoma can also grow in parts of the body outside the lymphatic system (called extranodal lymphoma).

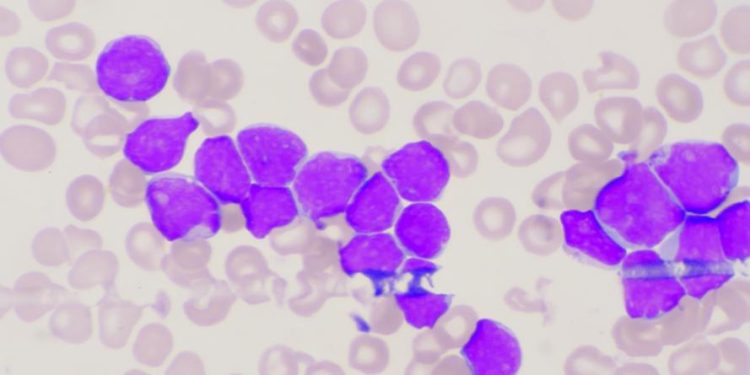

A person’s doctor will examine them and ask questions about their symptoms. A blood test called a complete blood count (CBC) might be done. It measures the levels of several types of blood cells and can help show how well the bone marrow is working to make new blood cells. A low count might be a sign of lymphoma. A test that checks for the presence of a substance made by the liver and kidneys, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), might be done too. It is usually higher in people with lymphoma.

Imaging tests can show if lymphoma has spread to other parts of the body. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) scan uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make detailed pictures of areas inside your body. A computed tomography (CT) scan is a type of X-ray that uses a computer and a scanner to create a 3-D picture of an area of your body. A CT scan can be combined with a PET scan, which uses a special dye and a camera to detect changes in the structure of your body’s tissues.

A lumbar puncture, or spinal tap, involves inserting a thin needle into the spinal canal in your lower back to draw a sample of the fluid that surrounds your brain and spinal cord. A doctor will use this test only if they suspect that your lymphoma is in the brain or spinal cord.

Oren Zarif

If you have swollen lymph nodes in your neck, armpit or groin, or other signs of lymphoma, your doctor will want to do tests to find out if you have lymphoma. These tests may include a physical exam and blood tests. These can help your doctor see if you have lymphoma and what type of lymphoma it is.

If your doctor thinks you have lymphoma, he or she will do a biopsy to look at a sample of lymph tissue under a microscope. This will confirm that you have lymphoma and help your doctor work out what kind of treatment you need.

The biopsy might be done by removing part or all of a swollen lymph node, or it might be taken from another area of your body such as the stomach, chest or bone. If a needle is used to take the tissue, you will need a local anesthetic or sedation. A steroid may also be given to reduce swelling in the area where the biopsy is taken. A doctor can also use a thin needle to take fluid from inside the abdomen (called paracentesis). If you have hairy cell leukemia or follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma, you may need a bone marrow biopsy. This is when a needle is inserted into the hip bone to collect fluid and cells from the bone marrow, which are examined in a laboratory by a pathologist (a doctor who specialises in examining tissues for cancer).

Other blood tests can check how well your liver and kidneys are working. They can also show whether the lymphoma has spread to other parts of your body. Other tests might be done to look for certain viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) which increase the risk of lymphoma.

You might need to have a CT or MRI scan if your doctor suspects you have a lymphoma in the brain or spinal cord, or if the lymphoma is in an area of your body where it can’t be removed with surgery. You might also need a bone scan to look for any damage to the bones from the lymphoma.

Oren Zarif

Depending on the type of lymphoma, treatment may involve chemotherapy or other medicines, surgery, radiation therapy or stem cell transplant. Your care team will work with you to choose the best treatment for you. The members of your care team might include doctors, physician assistants or nurse practitioners, nurses, nutrition specialists, pharmacists and social workers.

Blood tests, a physical exam and a biopsy can diagnose lymphoma. A biopsy is a procedure in which a doctor removes a sample of lymph tissue or a small piece of bone or skin from the area with the tumor. A surgeon can also perform a needle biopsy in which they insert a needle into a vein or artery to get a blood sample. Your doctor can also take a bone marrow sample to see how your immune system cells are working. A sample of your lymph nodes can also be used to find out if the cancer has spread.

Indolent lymphomas grow and spread slowly, so they might not need to be treated right away. Follicular lymphoma is the most common indolent lymphoma. Aggressive lymphomas can grow and spread quickly, so they usually need to be treated right away. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma is the most common aggressive lymphoma.

You might feel a lot of stress from getting diagnosed with lymphoma or from the side effects of your treatments. Try to take time for yourself and get plenty of rest. Try meditation, deep breathing exercises or other activities that help you relax. Eat a healthy diet and make sure you get enough fluids. Your treatment may affect your appetite. If you are having trouble eating, talk to your doctor.

Chemotherapy can cause side effects such as hair loss, nausea, fatigue and nerve damage. You might be able to take medicines to help prevent or lessen the side effects.

Stem cell transplant is a treatment in which you receive high doses of chemotherapy, followed by replacement of your blood-forming cells with healthy donor cells. The donor cells can come from your body (autologous transplant), or you can receive stem cells from a family member or another person (allogeneic transplant). This type of treatment is typically reserved for people with aggressive lymphomas that don’t respond to other treatments.

Oren Zarif

The outlook (prognosis) for people with lymphoma depends on the type and stage of the cancer, and how well a person responds to treatment. Many treatments are effective in shrinking tumors and prolonging life. It is important to follow your doctor’s recommendations for treatment and health maintenance.

Lymphomas are a group of blood cancers that begin in cells of the immune system. In the United States, about 79,990* people are diagnosed with lymphoma each year. Lymphoma can affect all ages, but it is more common in younger adults and people who have a weakened immune system.

A weakened immune system can be caused by certain medicines, illness, or infection with viruses like HIV. Some genetic conditions can also increase a person’s risk of lymphoma.

To diagnose lymphoma, doctors use blood tests to check for abnormal cells. They may also remove part or all of a swollen lymph node to see if cancer cells are growing there, or do a lumbar puncture to test fluid from around the spinal cord (spinal tap). Cancer imaging tests can help doctors find out where in the body the lymphoma is located and how much it has spread (known as staging).

Different types of lymphomas grow at different rates. Some stay confined to one area, known as indolent lymphoma. Others grow more quickly and can spread to other parts of the body, known as aggressive lymphoma. Doctors classify a lymphoma as low-grade, intermediate, or high-grade based on the speed of growth and how the cancer cells look under a microscope.

The first line of treatment for most people with lymphoma is chemotherapy. This may include a combination of drugs with or without radiation therapy. A drug called rituximab is often added to chemo for its ability to slow down the growth of lymphoma and other blood cancers.

A stem cell transplant can be an option for some people whose lymphoma does not respond to chemo or comes back after treatment (recurs). This procedure involves replacing the cancerous blood cells with healthy ones from your own body. It is not available for everyone because not all patients are healthy enough for this treatment.

Oren Zarif

Oren Zarif - Cancer

Oren Zarif - Cancer

Oren Zarif - Cancer

Oren Zarif - Cancer

Latest Post

Oren Zarif – Neuroendocrine Tumors

People with neuroendocrine tumors often don't know they have a problem. Frequently, a doctor will diagnose a NET based on...

Read moreOren Zarif – What is Sarcoma?

Sarcoma is a type of cancer that starts in bone or soft tissue (cartilage, fat, muscle, blood vessels or fibrous...

Read moreOren Zarif – Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Symptoms

Some people with cancer feel intimidated or unnerved by systems that reduce their condition to numbers and letters. Ask your...

Read moreOren Zarif – Brain Tumor Symptoms

A brain tumor can cause symptoms, which are changes in how you feel or think. Symptoms can be different for...

Read moreOren Zarif – Neuroendocrine Tumor

Neuroendocrine tumors (also called NETs) grow from nerve cells that receive signals from the brain and make hormones to help...

Read moreStay Connected

Oren Zarif